Orbital blow-out fracture

Updates to Article Attributes

Orbital blow-out fractures occur when there is a fracture of one of the walls of orbit but the orbital rim remains intact. This is typically caused by a direct blow to the central orbit from a fist or ball.

Epidemiology

The blow-out fracture is the most common type of orbital fracture and is usually due to trauma. This is reflected in the demographics: it is more prevalent in young men. Female patients who present with clinical details that do not match the fracture such as 'falling' should raise concerns about intimate partner violence 8.

Clinical presentation

Orbital blow-out fractures are usually the result of a direct blow to the orbit, which causes a sudden increase in intraorbital pressure. Decompression then occurs by fracture of one or more of the bounding walls of the orbit.

Although the causative trauma is usually substantial, presentation and diagnosis may be delayed in the setting of extensive soft tissue swelling and (by definition) an intact orbital rim. In particular, clinical findings of diplopia and restricted ocular motion may be temporarily masked by intraorbital swelling which can compensate for the traumatically-expanded osseous orbital volume 1.

Clinical findings associated with orbital blow-out fracture may include:

- enophthalmos: due to increased orbital volume

- diplopia: due to extraocular muscle entrapment

- orbital emphysema: especially when the fracture is into an adjacent paranasal sinus (see: black eyebrow sign)

- malar region numbness: due to injury to the infraorbital nerve

- hypoglobus

Pathology

Different types of blow-out fracture

Blow-out fractures can occur through one or more of the orbital walls:

- inferior (floor)

- medial wall (lamina papyracea)

- superior (roof)

- lateral wall

Inferior blow-out fracture

Inferior blow-out fractures are the most common. Orbital fat prolapses into the maxillary sinus and may be joined by prolapse of the inferior rectus muscle. In children, the fracture may spring back into place (see trapdoor fracture). Most fractures occur in the floor posterior and medial to the infraorbital groove 2.

In ~50% of cases, inferior blow-out fractures are associated with fractures of the medial wall 3.

Medial blow-out fracture

Medial blow-out fractures are the second most common type, occurring through the lamina papyracea. Orbital fat and the medial rectus muscle may prolapse into the ethmoid air cells.

Superior blow-out fracture

Pure superior blow-out fractures (without associated orbital rim fracture) are uncommon. They are usually seen in patients with pneumatisation of the orbital roof 2,4.

Fractures may only involve the sinus, the anterior cranial fossa (less common), or both the sinus and anterior cranial fossa. Fractures communicating with the anterior cranial fossa are at risk for CSF leak and meningitis.

Lateral blow-out fracture

Pure lateral blow-out fractures are rare, as the bone is thick and bounded by muscle. If fractures are present they are usually associated with orbital rim or other significant craniofacial injuries.

Radiographic features

Plain radiograph

Radiographs are not recommended for the assessment of facial trauma due to poor sensitivity to injury.

However, if they are obtained, the diagnosis of fractures involving the inferior or medial wall may be suspected by visualisation of fluid with the maxillary sinus and ethmoidal air cells, respectively 3. A few named signs have been described:

- orbital emphysema may result in a black eyebrow sign

- inferior herniation of the intraorbital fat may result in a "teardrop" sign

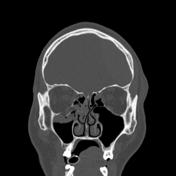

CT

CT is the modality of choice for the assessment of the facial skeleton. A full assessment does not require the administration of contrast. Ideally, the acquisition should be performed using the thinnest detector settings, enabling thin-slice reconstructions along three orthogonal planes with a bone algorithm. Additional soft tissue algorithm reconstructions using larger slice thickness and 3D volumetric reconstruction are useful for assessing associated soft tissue injury and gauging facial asymmetry, respectively.

In addition to evaluating the location and extent of fracture(s), other features requiring assessment and report include:

- presence of intraorbital (usually extraconal) haemorrhage: may result in stretching or compression of the optic nerve

- globe injury/rupture

- extraocular muscle entrapment: suspected if there is an acute change in angle of the muscle 3

- prolapse of orbital fat

Several imaging features are associated with late enophthalmos 1:

- surface area of fracture ≥2 cm2 5

- ≥25-50% involvement of inferior or medial orbital walls

- collapse of internal orbital buttress or convex junctional bulge

- internal orbital buttress located at the union between medial and inferior orbital walls

- the convex junctional bulge is the posterior continuation of the internal orbital buttress, supporting the orbital contents from posterior

- intraorbital soft tissue herniation volume ≥1.5 mL 6

- a linear relationship between the volume of intraorbital contents and depth of enophthalmos 1

Treatment and prognosis

Management of any globe injury generally takes precedence over fractures 1.

In general, there has been a trend toward conservative management of orbital blow-out fractures. Initial post-traumatic diplopia or extraocular muscle impairment may improve over time, as oedema or muscle injury resolves 1,7.

For orbital fractures without associated globe injury, immediate surgical management is reserved for cases where the risk of chronic impairment outweighs the risks of surgery. Although the modern transconjunctival incision technique has decreased eyelid complications associated with cutaneous eyelid approaches, surgery in the acute setting remains associated with the risk of an iatrogenic eyelid, extraocular muscle, or optic nerve injury 1,7. This is in part because soft tissue swelling may require increased surgical exposure and retraction 1.

Potential indications for surgical repair include:

- significant enophthalmos

- significant diplopia

- muscle entrapment, especially with "trapdoor fracture" in children

- large area fractures

The timing of surgery is a subject of debate. Many surgeons elect for semi-delayed or late repair. This allows for assessment for noticeable enophthalmos, diplopia, or extraocular muscle impairment once the swelling has subsided 1,7. This must be balanced against the risk of developing fibrosis and more permanent structural impairment with longer delayed management 1.

Differential diagnosis

For non-acute medial orbital blow-out fractures consider:

See also

-<p><strong>Orbital blow-out fractures</strong> occur when there is a fracture of one of the walls of <a href="/articles/orbit">orbit</a> but the orbital rim remains intact. This is typically caused by a direct blow to the central orbit from a fist or ball.</p><h4>Epidemiology</h4><p>The blow-out fracture is the most common type of <a href="/articles/orbital-fracture">orbital fracture</a> and is usually due to trauma. This is reflected in the demographics: it is more prevalent in young men. Female patients who present with clinical details that do not match the fracture such as 'falling' should raise concerns about <a href="/articles/intimate-partner-violence">i</a><a href="/articles/intimate-partner-violence">ntimate partner violence</a> <sup>8</sup>.</p><h4>Clinical presentation</h4><p>Orbital blow-out fractures are usually the result of a direct blow to the orbit, which causes a sudden increase in intraorbital pressure. Decompression then occurs by fracture of one or more of the bounding walls of the orbit.</p><p>Although the causative trauma is usually substantial, presentation and diagnosis may be delayed in the setting of extensive soft tissue swelling and (by definition) an intact orbital rim. In particular, clinical findings of <a href="/articles/diplopia">diplopia</a> and restricted ocular motion may be temporarily masked by intraorbital swelling which can compensate for the traumatically-expanded osseous orbital volume <sup>1</sup>.</p><p>Clinical findings associated with orbital blow-out fracture may include:</p><ul>-<li>-<a href="/articles/enophthalmos">enophthalmos</a>: due to increased orbital volume</li>-<li>diplopia: due to extraocular muscle entrapment</li>-<li>-<a href="/articles/orbital-emphysema">orbital emphysema</a>: especially when the fracture is into an adjacent paranasal sinus (see: <a href="/articles/black-eyebrow-sign">black eyebrow sign</a>)</li>-<li>malar region numbness: due to injury to the <a href="/articles/infraorbital-nerve-2">infraorbital nerve</a>-</li>-<li><a href="/articles/hypoglobus">hypoglobus</a></li>-</ul><h4>Pathology</h4><h5>Different types of blow-out fracture</h5><p>Blow-out fractures can occur through one or more of the orbital walls:</p><ul>-<li>inferior (floor)</li>-<li>medial wall (lamina papyracea)</li>-<li>superior (roof)</li>-<li>lateral wall</li>-</ul><h6>Inferior blow-out fracture</h6><p>Inferior blow-out fractures are the most common. Orbital fat prolapses into the maxillary sinus and may be joined by prolapse of the <a href="/articles/inferior-rectus-muscle">inferior rectus muscle</a>. In children, the fracture may spring back into place (see <a href="/articles/trapdoor-fracture">trapdoor fracture</a>). Most fractures occur in the floor posterior and medial to the infraorbital groove <sup>2</sup>.</p><p>In ~50% of cases, inferior blow-out fractures are associated with fractures of the medial wall <sup>3</sup>.</p><h6>Medial blow-out fracture</h6><p>Medial blow-out fractures are the second most common type, occurring through the lamina papyracea. Orbital fat and the <a href="/articles/medial-rectus-muscle">medial rectus muscle</a> may prolapse into the ethmoid air cells.</p><h6>Superior blow-out fracture</h6><p>Pure superior blow-out fractures (without associated orbital rim fracture) are uncommon. They are usually seen in patients with pneumatisation of the orbital roof <sup>2,4</sup>.</p><p>Fractures may only involve the sinus, the anterior cranial fossa (less common), or both the sinus and anterior cranial fossa. Fractures communicating with the anterior cranial fossa are at risk for <a href="/articles/csf-rhinorrhoea">CSF leak</a> and <a href="/articles/leptomeningitis">meningitis</a>.</p><h6>Lateral blow-out fracture</h6><p>Pure lateral blow-out fractures are rare, as the bone is thick and bounded by muscle. If fractures are present they are usually associated with orbital rim or other significant craniofacial injuries.</p><h4>Radiographic features</h4><h5>Plain radiograph</h5><p>Radiographs are not recommended for the assessment of facial trauma due to poor sensitivity to injury.</p><p>However, if they are obtained, the diagnosis of fractures involving the inferior or medial wall may be suspected by visualisation of fluid with the maxillary sinus and ethmoidal air cells, respectively <sup>3</sup>. A few named signs have been described:</p><ul>-<li>orbital emphysema may result in a <a href="/articles/black-eyebrow-sign">black eyebrow sign</a>-</li>-<li>inferior herniation of the intraorbital fat may result in a "<a href="/articles/teardrop-sign-inferior-orbital-wall-fracture">teardrop</a>" sign</li>-</ul><h5>CT</h5><p>CT is the modality of choice for the assessment of the facial skeleton. A full assessment does not require the administration of contrast. Ideally, the acquisition should be performed using the thinnest detector settings, enabling thin-slice reconstructions along three orthogonal planes with a bone algorithm. Additional soft tissue algorithm reconstructions using larger slice thickness and 3D volumetric reconstruction are useful for assessing associated soft tissue injury and gauging facial asymmetry, respectively.</p><p>In addition to evaluating the location and extent of fracture(s), other features requiring assessment and report include:</p><ul>-<li>presence of intraorbital (usually <a href="/articles/extraconal-haematoma">extraconal</a>) haemorrhage: may result in stretching or compression of the optic nerve</li>-<li>globe injury/<a href="/articles/globe-rupture">rupture</a>-</li>-<li>extraocular muscle entrapment: suspected if there is an acute change in angle of the muscle <sup>3</sup>-</li>-<li>prolapse of orbital fat</li>-</ul><p>Several imaging features are associated with late enophthalmos <sup>1</sup>:</p><ul>-<li>surface area of fracture ≥2 cm<sup>2</sup> <sup>5</sup>-</li>-<li>≥25-50% involvement of inferior or medial orbital walls</li>-<li>collapse of internal orbital buttress or convex junctional bulge<ul>-<li>internal orbital buttress located at the union between medial and inferior orbital walls</li>-<li>the convex junctional bulge is the posterior continuation of the internal orbital buttress, supporting the orbital contents from posterior</li>-</ul>-</li>-<li>intraorbital soft tissue herniation volume ≥1.5 mL <sup>6</sup><ul><li>a linear relationship between the volume of intraorbital contents and depth of enophthalmos <sup>1</sup>-</li></ul>-</li>-</ul><h4>Treatment and prognosis</h4><p>Management of any globe injury generally takes precedence over fractures <sup>1</sup>.</p><p>In general, there has been a trend toward conservative management of orbital blow-out fractures. Initial post-traumatic diplopia or extraocular muscle impairment may improve over time, as oedema or muscle injury resolves <sup>1,7</sup>.</p><p>For orbital fractures without associated globe injury, immediate surgical management is reserved for cases where the risk of chronic impairment outweighs the risks of surgery. Although the modern transconjunctival incision technique has decreased eyelid complications associated with cutaneous eyelid approaches, surgery in the acute setting remains associated with the risk of an iatrogenic eyelid, extraocular muscle, or optic nerve injury <sup>1,7</sup>. This is in part because soft tissue swelling may require increased surgical exposure and retraction <sup>1</sup>.</p><p>Potential indications for surgical repair include:</p><ul>-<li>significant enophthalmos</li>-<li>significant diplopia</li>-<li>muscle entrapment, especially with "<a href="/articles/trapdoor-fracture">trapdoor fracture</a>" in children</li>-<li>large area fractures</li>- +<p><strong>Orbital blow-out fractures</strong> occur when there is a fracture of one of the walls of <a href="/articles/orbit">orbit</a> but the orbital rim remains intact. This is typically caused by a direct blow to the central orbit from a fist or ball.</p><h4>Epidemiology</h4><p>The blow-out fracture is the most common type of <a href="/articles/orbital-fracture">orbital fracture</a> and is usually due to trauma. This is reflected in the demographics: it is more prevalent in young men. Female patients who present with clinical details that do not match the fracture such as 'falling' should raise concerns about <a href="/articles/intimate-partner-violence">i</a><a href="/articles/intimate-partner-violence">ntimate partner violence</a> <sup>8</sup>.</p><h4>Clinical presentation</h4><p>Orbital blow-out fractures are usually the result of a direct blow to the orbit, which causes a sudden increase in intraorbital pressure. Decompression then occurs by fracture of one or more of the bounding walls of the orbit.</p><p>Although the causative trauma is usually substantial, presentation and diagnosis may be delayed in the setting of extensive soft tissue swelling and (by definition) an intact orbital rim. In particular, clinical findings of <a href="/articles/diplopia">diplopia</a> and restricted ocular motion may be temporarily masked by intraorbital swelling which can compensate for the traumatically-expanded osseous orbital volume <sup>1</sup>.</p><p>Clinical findings associated with orbital blow-out fracture may include:</p><ul>

- +<li>

- +<a href="/articles/enophthalmos">enophthalmos</a>: due to increased orbital volume</li>

- +<li>diplopia: due to extraocular muscle entrapment</li>

- +<li>

- +<a href="/articles/orbital-emphysema">orbital emphysema</a>: especially when the fracture is into an adjacent paranasal sinus (see: <a href="/articles/black-eyebrow-sign">black eyebrow sign</a>)</li>

- +<li>malar region numbness: due to injury to the <a href="/articles/infraorbital-nerve-2">infraorbital nerve</a>

- +</li>

- +<li><a href="/articles/hypoglobus">hypoglobus</a></li>

- +</ul><h4>Pathology</h4><h5>Different types of blow-out fracture</h5><p>Blow-out fractures can occur through one or more of the orbital walls:</p><ul>

- +<li>inferior (floor)</li>

- +<li>medial wall (lamina papyracea)</li>

- +<li>superior (roof)</li>

- +<li>lateral wall</li>

- +</ul><h6>Inferior blow-out fracture</h6><p>Inferior blow-out fractures are the most common. Orbital fat prolapses into the maxillary sinus and may be joined by prolapse of the <a href="/articles/inferior-rectus-muscle">inferior rectus muscle</a>. In children, the fracture may spring back into place (see <a href="/articles/trapdoor-fracture">trapdoor fracture</a>). Most fractures occur in the floor posterior and medial to the infraorbital groove <sup>2</sup>.</p><p>In ~50% of cases, inferior blow-out fractures are associated with fractures of the medial wall <sup>3</sup>.</p><h6>Medial blow-out fracture</h6><p>Medial blow-out fractures are the second most common type, occurring through the lamina papyracea. Orbital fat and the <a href="/articles/medial-rectus-muscle">medial rectus muscle</a> may prolapse into the ethmoid air cells.</p><h6>Superior blow-out fracture</h6><p>Pure superior blow-out fractures (without associated orbital rim fracture) are uncommon. They are usually seen in patients with pneumatisation of the orbital roof <sup>2,4</sup>.</p><p>Fractures may only involve the sinus, the anterior cranial fossa (less common), or both the sinus and anterior cranial fossa. Fractures communicating with the anterior cranial fossa are at risk for <a href="/articles/csf-rhinorrhoea">CSF leak</a> and <a href="/articles/leptomeningitis">meningitis</a>.</p><h6>Lateral blow-out fracture</h6><p>Pure lateral blow-out fractures are rare, as the bone is thick and bounded by muscle. If fractures are present they are usually associated with orbital rim or other significant craniofacial injuries.</p><h4>Radiographic features</h4><h5>Plain radiograph</h5><p>Radiographs are not recommended for the assessment of facial trauma due to poor sensitivity to injury.</p><p>However, if they are obtained, the diagnosis of fractures involving the inferior or medial wall may be suspected by visualisation of fluid with the maxillary sinus and ethmoidal air cells, respectively <sup>3</sup>. A few named signs have been described:</p><ul>

- +<li>orbital emphysema may result in a <a href="/articles/black-eyebrow-sign">black eyebrow sign</a>

- +</li>

- +<li>inferior herniation of the intraorbital fat may result in a "<a href="/articles/teardrop-sign-inferior-orbital-wall-fracture">teardrop</a>" sign</li>

- +</ul><h5>CT</h5><p>CT is the modality of choice for the assessment of the facial skeleton. A full assessment does not require the administration of contrast. Ideally, the acquisition should be performed using the thinnest detector settings, enabling thin-slice reconstructions along three orthogonal planes with a bone algorithm. Additional soft tissue algorithm reconstructions using larger slice thickness and 3D volumetric reconstruction are useful for assessing associated soft tissue injury and gauging facial asymmetry, respectively.</p><p>In addition to evaluating the location and extent of fracture(s), other features requiring assessment and report include:</p><ul>

- +<li>presence of intraorbital (usually <a href="/articles/extraconal-haematoma">extraconal</a>) haemorrhage: may result in stretching or compression of the optic nerve</li>

- +<li>globe injury/<a href="/articles/globe-rupture">rupture</a>

- +</li>

- +<li>extraocular muscle entrapment: suspected if there is an acute change in angle of the muscle <sup>3</sup>

- +</li>

- +<li>prolapse of orbital fat</li>

- +</ul><p>Several imaging features are associated with late enophthalmos <sup>1</sup>:</p><ul>

- +<li>surface area of fracture ≥2 cm<sup>2</sup> <sup>5</sup>

- +</li>

- +<li>≥25-50% involvement of inferior or medial orbital walls</li>

- +<li>collapse of internal orbital buttress or convex junctional bulge<ul>

- +<li>internal orbital buttress located at the union between medial and inferior orbital walls</li>

- +<li>the convex junctional bulge is the posterior continuation of the internal orbital buttress, supporting the orbital contents from posterior</li>

- +</ul>

- +</li>

- +<li>intraorbital soft tissue herniation volume ≥1.5 mL <sup>6</sup><ul><li>a linear relationship between the volume of intraorbital contents and depth of enophthalmos <sup>1</sup>

- +</li></ul>

- +</li>

- +</ul><h4>Treatment and prognosis</h4><p>Management of any globe injury generally takes precedence over fractures <sup>1</sup>.</p><p>In general, there has been a trend toward conservative management of orbital blow-out fractures. Initial post-traumatic diplopia or extraocular muscle impairment may improve over time, as oedema or muscle injury resolves <sup>1,7</sup>.</p><p>For orbital fractures without associated globe injury, immediate surgical management is reserved for cases where the risk of chronic impairment outweighs the risks of surgery. Although the modern transconjunctival incision technique has decreased eyelid complications associated with cutaneous eyelid approaches, surgery in the acute setting remains associated with the risk of an iatrogenic eyelid, extraocular muscle, or optic nerve injury <sup>1,7</sup>. This is in part because soft tissue swelling may require increased surgical exposure and retraction <sup>1</sup>.</p><p>Potential indications for surgical repair include:</p><ul>

- +<li>significant enophthalmos</li>

- +<li>significant diplopia</li>

- +<li>muscle entrapment, especially with "<a href="/articles/trapdoor-fracture">trapdoor fracture</a>" in children</li>

- +<li>large area fractures</li>

References changed:

- 1. Dreizin D, Nam A, Diaconu S, Bernstein M, Bodanapally U, Munera F. Multidetector CT of Midfacial Fractures: Classification Systems, Principles of Reduction, and Common Complications. Radiographics. 2018;38(1):248-74. <a href="https://doi.org/10.1148/rg.2018170074">doi:10.1148/rg.2018170074</a> - <a href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29320322">Pubmed</a>

- 2. Curtin H, Wolfe P, Schramm V. Orbital Roof Blow-Out Fractures. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1982;139(5):969-72. <a href="https://doi.org/10.2214/ajr.139.5.969">doi:10.2214/ajr.139.5.969</a> - <a href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6981984">Pubmed</a>

- 3. Zilkha A. Computed Tomography of Blow-Out Fracture of the Medial Orbital Wall. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1981;137(5):963-5. <a href="https://doi.org/10.2214/ajr.137.5.963">doi:10.2214/ajr.137.5.963</a> - <a href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6975022">Pubmed</a>

- 4. Rothman M, Simon E, Zoarski G, Zagardo M. Superior Blowout Fracture of the Orbit: The Blowup Fracture. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1998;19(8):1448-9. <a href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8338674">PMC8338674</a> - <a href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9763375">Pubmed</a>

- 7. Chung S & Langer P. Pediatric Orbital Blowout Fractures. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2017;28(5):470-6. <a href="https://doi.org/10.1097/ICU.0000000000000407">doi:10.1097/ICU.0000000000000407</a> - <a href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28797015">Pubmed</a>

- 8. Alessandrino F, Keraliya A, Lebovic J et al. Intimate Partner Violence: A Primer for Radiologists to Make the “Invisible” Visible. Radiographics. 2020;40(7):2080-97. <a href="https://doi.org/10.1148/rg.2020200010">doi:10.1148/rg.2020200010</a> - <a href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33006922">Pubmed</a>

- 1. Dreizin D, Nam AJ, Diaconu SC et-al. Multidetector CT of Midfacial Fractures: Classification Systems, Principles of Reduction, and Common Complications. (2018) Radiographics : a review publication of the Radiological Society of North America, Inc. 38 (1): 248-274. <a href="https://doi.org/10.1148/rg.2018170074">doi:10.1148/rg.2018170074</a> - <a href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29320322">Pubmed</a> <span class="ref_v4"></span>

- 2. Curtin HD, Wolfe P, Schramm V. Orbital roof blow-out fractures. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1982;139 (5): 969-72. <a href="http://www.ajronline.org/cgi/content/citation/139/5/969">AJR Am J Roentgenol (citation)</a> [<a href="http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6981984">pubmed citation</a>]

- 3. Zilkha A. Computed tomography of blow-out fracture of the medial orbital wall. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1981;137 (5): 963-5. <a href="http://www.ajronline.org/cgi/content/citation/137/5/963">AJR Am J Roentgenol (citation)</a> [<a href="http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6975022">pubmed citation</a>]

- 4. Rothman MI, Simon EM, Zoarski GH et-al. Superior blowout fracture of the orbit: the blowup fracture. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1998;19 (8): 1448-9. <a href="http://www.ajnr.org/cgi/content/abstract/19/8/1448">AJNR Am J Neuroradiol (abstract)</a> [<a href="http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9763375">pubmed citation</a>]

- 7. Chung SY, Langer PD. Pediatric orbital blowout fractures. (2017) Current opinion in ophthalmology. 28 (5): 470-476. <a href="https://doi.org/10.1097/ICU.0000000000000407">doi:10.1097/ICU.0000000000000407</a> - <a href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28797015">Pubmed</a> <span class="ref_v4"></span>

- 8. Alessandrino Francesco, Abhishek Keraliya and Jordan Lebovic et al. "Intimate Partner Violence: A Primer for Radiologists to Make the “Invisible” Visible". RadioGraphics 40, no. 7 (2020): 2080-2097. <a href="http://dx.doi.org/10.1148/rg.2020200010" target="_blank">. doi:10.1148/rg.2020200010</a>.

Image 1 CT (non-contrast) ( destroy )

Image 1 MRI (T1) ( destroy )

Image 1 CT (bone window) ( destroy )

Image 1 CT (bone window) ( destroy )

Image 1 CT (non-contrast) ( update )

Image 2 CT (bone window) ( destroy )

Image 2 CT (non-contrast) ( destroy )

Image 2 CT (bone window) ( destroy )

Image 2 CT (non-contrast) ( update )

Image 3 CT (non-contrast) ( update )

Image 4 CT (bone window) ( update )

Image 5 CT (bone window) ( update )

Image 6 CT (bone window) ( destroy )

Image 6 CT (non-contrast) ( destroy )

Image 6 CT (non-contrast) ( update )

Image 7 X-ray (Frontal) ( update )

Image 8 CT (non-contrast) ( destroy )

Image 8 CT (bone window) ( destroy )

Image 8 CT (bone window) ( destroy )

Image 8 X-ray (Frontal) ( update )

Image 9 CT (bone window) ( destroy )

Image 9 CT (bone window) ( destroy )

Image 9 CT (non-contrast) ( destroy )

Image 9 CT (bone window) ( destroy )

Image 9 CT (bone window) ( destroy )

Image 9 CT (non-contrast) ( destroy )

Image 9 X-ray (Frontal) ( update )

Image 10 MRI (STIR) ( update )

Image 11 CT (non-contrast) ( update )

Image 12 CT (non-contrast) ( update )

Image 13 CT (non-contrast) ( update )

Image 14 CT (bone window) ( update )

Unable to process the form. Check for errors and try again.

Unable to process the form. Check for errors and try again.